May 8, 2011

Before Mr. Bagel

Jewish merchants of Portland past

by Zack Barowitz

photo/Zachary Barowitz

In the mid-1970s, my dad landed a summer teaching job at what was then the Portland School of Art (now Maine College of Art). We were new to Portland – summer people from New York City. Over the next several years, we gradually found the handful of Jewish merchants downtown and in the Old Port. Among them were:

- Levinsky’s, a large rabbit warren of a clothing store where our Portland friends would do their back-to-school shopping. They’d buy Levi’s corduroys and web belts (denim jeans were prohibited at Cheverus).

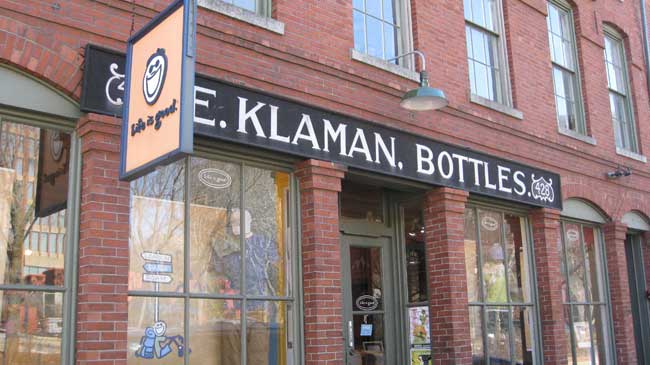

- E. Klaman Bottles, on Fore Street. Klaman’s was well stocked with antique bottles, but as I recall, the proprietor showed very little interest in selling them and had a general distaste for customer service.

- Zeitman’s Grocery Store, also on Fore Street. Mr. Zeitman bemused my father one day by chastising him for buying bread from the Port Bakehouse, a proto-yuppie bakery. “What are you buying that crap for? This is the finest bread you can buy!” he said, pointing to the plastic bags of soft J.J. Nissen loaves.

- Cinamon Brothers, in Gorham’s Corner (where John Ford’s statue sits), was a multi-story used furniture store packed with dusty wares. The store’s proprietors later provided, perhaps unfairly, my mental image of the Collyer brothers when I first heard of those famous hoarders later in life.

- Sukowitch’s Hardware, in the Old Port, was another fave. My parents got a kick out of finding merchandise that had been there since the ’50s, still in its original box and available at original prices.

- The Model Market, on Middle Street, Portland’s first specialty foods store, sold imported delicacies and had a good wine selection. At the time, champagne was enough of a novelty item that when proprietor Saul Goldberg sold my mom a bottle, he advised her to “chill it.”

photo/Zachary Barowitz

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, Portland was overwhelming white and predominantly Christian. My parents recall the curious word repeatedly used by the real estate broker who was showing them summer rental properties in Prouts Neck.

“This is a very exclusive area,” said the broker.

“That’s OK,” said my mom.

“This is also an exclusive neighborhood.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And this too is an exclusive section.”

“Well, that is fine,” my mom said, “but we aren’t particularly ‘exclusive’ people.”

It wasn’t until afterward that they realized “exclusive” meant “no Jews.” Still, it was nice of the broker to take the time to show us the properties.

Coming from New York, where everyone was Jewish, I felt quite alien in Portland. Yet people weren’t prejudiced against me because I was Jewish. Rather, the discrimination I suffered was for being a Yankee fan. Perhaps it amounted to the same thing.

As for the Jewish business owners I saw in Portland, I assumed they had just taken a wrong turn one day and ended up here. In fact, that is not the case.

photo/courtesy City of Portland

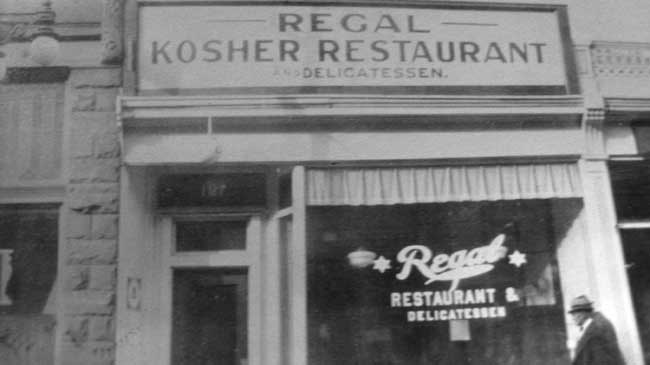

From the early 1900s to the early ’60s, Portland’s Jewish community was not only sizable, but visible — visible not by devil horns or black hats and beards, but by the merchant district in the area of Middle, Fore, and Franklin Streets. Bakeries, butchers, tailors, shoemakers, and even kosher restaurants served the community. One old-timer I spoke with told me there were three bakeries when he was a kid: “One you went to for their bread, another for their pastries, and the third was pretty good with both.”

Jews were also active in the city’s banking and manufacturing sectors. One colorful story I heard in the course of my research was about Si Glazer, a clothing manufacturer who got a contract to make t-shirts for prison inmates. The order was for mediums, but Si had a lot of small shirts on hand, so he tore out the labels that read “small” and replaced them with labels for mediums, figuring this was one set of customers who were not in a position to complain.

This research wasn’t easy. (There are bound to be challenges when your subjects are elderly Jews.) One gentleman I called deterred me from conducting an interview by saying, “My memory is not too good.”

“Well,” I told him, “a little memory is a lot more than nothing.”

“Can you send me something that explains what you are doing any better?” he asked.

“Yes. How would you like me to send it?”

“How do I want you to send it? U.S. mail!”

“Very well,” I said. “May I have your address?”

“Well, how did you get my phone number?”

“From the phone book.”

“Well, you can get my address from there, too!”

Apart from collecting lively stories, I wanted to answer two basic questions. The first: Where did Portland’s Jewish merchants come from?

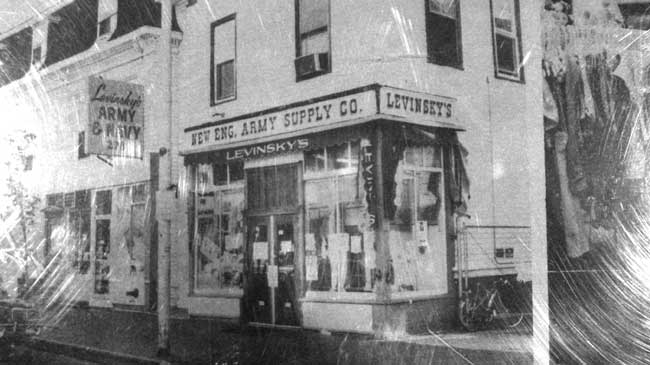

Most were immigrants from Eastern Europe who came through Ellis Island and made their way up from New York and Boston. Many were peddlers, like the Russian who started the New England Army Supply Company by bringing surplus military clothing to town via horse and team and selling it out of a barn on Oxford Street. Another early peddler eschewed the pushcart for a rowboat and made his living serving the ships.

photo/courtesy City of Portland

Throughout the 1940s and ’50s, the Jewish mercantile community remained strong, though also insular, as many jobs were not available to Jews. One is reminded of the famous speech delivered by Rod Steiger in The Pawnbroker, a 1964 film based on the novel by Edward Lewis Wallant:

You go out and you buy a piece of cloth and you cut that cloth in two and you go out and sell it for a penny more than you paid for it. Then you run right out and buy another piece of cloth, cut it into three pieces and sell it for three pennies’ profit … You just go on and on and on, repeating this process over the centuries, over and over, and suddenly you make a grand discovery: you have a mercantile heritage!

In the 1960s, the New England Army Supply Company changed its name to Levinsky’s. “President Kennedy made everyone a first-class American,” said Philip Levinsky, namesake and grandson of the company’s founder, explaining the name change. And besides, in retail, the shorter name was a plus.

(That said, not everything Kennedy did was good for business. The president did not wear a hat, Levinsky noted, a fact that effectively ended that fashion among men, rendering Levinsky’s large inventory of hats practically worthless.)

A fixture on Congress Street for most of the 20th century, Levinsky’s expanded two decades ago, adding several more locations, but is now down to just one — in Windham. Which brings me to my second question. Where did all the Jewish merchants go?

Urban renewal played a part in their disappearance from downtown. When Franklin Street became Franklin Arterial half a century ago, ethnic neighborhoods partially bulldozed and cut off by the urban highway soon lost their identities.

However, in the case of Portland’s Jewish merchant class, social liberalization and access to a broader range of professions were equal, if not stronger, factors. Today just two Jewish-owned businesses remain from the old days: Hub Furniture, on Fore Street, and Wigon Office Supply, on Free Street. Everyone else wandered away when they got the opportunity, as is characteristic of the Diaspora, though they didn’t necessarily wander very far.

Woodford’s Corner is the new hub of Jewish social life in Portland. The off-peninsula neighborhood is home to the Levey Day School, two synagogues, the Jewish Community Alliance, a new mikvah (Mikvat Shalom, a Jewish ritual menstrual bath), and a Jewish funeral home.

During my interviews with the old-timers, I didn’t sense much sentimentality about the old Jewish merchant district. It’s remembered more as a kind of occupational ghetto than as the old neighborhood.

Perhaps it was too exclusive for its own good.

An earlier version of this essay was published as part of Colby’s Maine Jewish History Project. For more information about the project, visit web.colby.edu/jewsinmaine.